Much of Oregon’s forestry history is deeply intertwined with its Indigenous history. Keep reading for a deep dive into the Donation Land Act of 1850 and how it affected foresters and Indigenous Peoples alike.

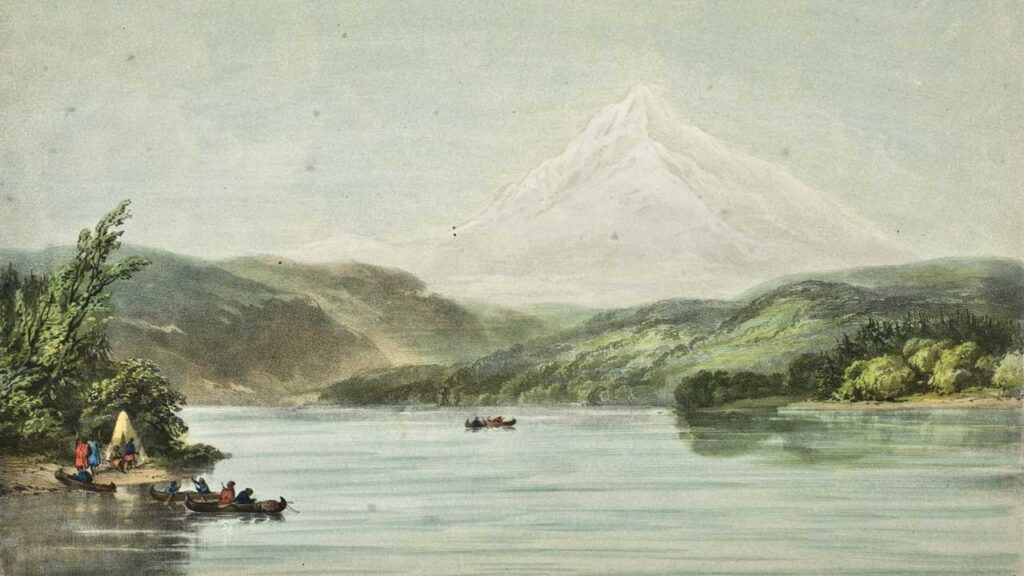

For thousands of years, Oregon was only home to tribes of Indigenous Peoples who lived symbiotically with the land. As European settlers spread throughout the U.S., they forcibly removed Native Peoples from their land and relocated them onto reservations. Often, these reservations were not on the tribe’s original ancestral lands. Oregon’s timber history is deeply intertwined with this relocation and displacement of Indigenous Peoples and tribes.

As the U.S. Government removed Indigenous Peoples out of their land for the re-allocation to white settlers, conflict erupted between these white settlers and Native Peoples; many tribes did not survive these conflicts. In 1854, U.S. Army troops forcibly relocated most surviving tribal bands to a newly established coastal reservation. The Act expired in 1855, but the damage done to tribes was irreparable.

The Donation Land Act was one way of displacing tribes and Indigenous People from prime land. Another way the U.S. Government removed tribes and Indigenous People from their lands was though treaties. Don Motinac, in his talk at Oregon State University, discusses the “trail of tears” endured by the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Suislaw peoples during their forced relocation. Motinac refers to Oregon as the “the termination state for tribes.”

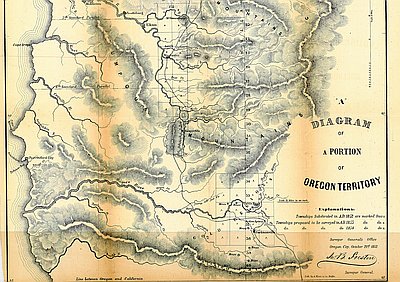

Professor David Johnson, Ph.D. calls the Donation Land Act of 1850 “the means by which Oregon was conquered by the United States and integrated into an emerging continental Nation-State” in his talk through the Oregon Historical Society.

The settlement of white citizens in Oregon paved the way for the state’s future. Oregon officially became a state in 1859, as white settlers filled the territory. However, the violence and relocation meant the area’s Native population had been radically diminished.

Out of the 23 tribes that were located in present-day Oregon when white settlers first started moving to the state only 9 federally recognized tribes remain in the state today: The Burns Paiute Tribe; the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Suislaw Indians; The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde; The Confederated tribes of Slietz; The Confederated tribes of the Umatilla Reservation; The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs; The Coquille Indian Tribe; The Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians; and The Klamath Tribe.

The existing tribes in Oregon play a large role in forestry and forest maintenance. It is immeasurably important to recognize the Indigenous forestry history within Oregon and the lesser known facts of Oregon’s timber history. Like all of Portland, World Forestry Center sits on Indigenous land. For our land acknowledgement, take a look here.

*We have chosen to capitalize the terms Native Peoples and Indigenous Peoples out of respect for the People we are referring to.

Sources & Further Reading

http://www.native-languages.org/oregon.htm

https://www.ohs.org/events/how-the-donation-land-act-created-the-state-of-oregon.cfm

https://www.ohs.org/events/two-hundred-years-of-changes-to-native-peoples-of-western-oregon.cfm

https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/Pages/records/aids-land_federal.aspx

https://www.willametteheritage.org/assets/LaRC/bios_histories/Oregon_Donation_and_Land_Law.pdf

https://oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/oregon_donation_land_act/#.XzGzN2pKh0s